Jörg Neugschwender

Public pension systems follow different state traditions. In this blog, I look at the implications of these different pathways for gender gaps in the pension income distribution. The recent ‘Pension Adequacy Report 2018‘ by the European Commission revealed that the gender gap in pensions in the EU (36%) is […] twice the gender gap in pay (16.3%). In order to illustrate cross-national differences in pension outcomes, I selected four countries, each representing a rather distinct pathway in pension provision: Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom.

Before analysing the different pension outcomes in these four countries, let me briefly highlight the core differences in pension system design. Pension schemes are set up to provide two main goals – poverty prevention and income maintenance, in the sense of replacement of a certain degree of earnings during the retirement phase. A common distinction is analogously made into two ideal types of pension system design: Beveridgean (targeted pensions) and Bismarckian (earnings-related) public pension schemes.

The Beveridge type pension schemes provide only the first-tier of social security among the elderly; these schemes are set up to prevent poverty. Different proto-types of Beveridgean schemes provide minimum pensions either based on means-tested pensions (e.g. Finland), or based on employment years (e.g. the United Kingdom), or based on residency in the country (e.g. Netherlands and Denmark).

The Bismarckian schemes are more generally linked to the employment career (e.g. Germany, Austria, and Italy); own accumulated contributions and contributions paid by employers mostly define pension outcomes. These schemes are similarly known as pay-as-you-go schemes; the higher accumulated contributions, the higher pension annuities. Thus, besides the goal of poverty prevention (first-tier), these schemes also provide income maintenance (second-tier) of previous earnings. There might be redistributive elements included to support specific groups in need, for example credits for taking into account different periods of inactivity such as child raising, invalidity, or unemployment. On the other hand, these contribution-based Bismarckian schemes might also cross-finance payments of minimum pensions for those whose contributions were insufficient to guarantee a self-sufficient protection.

Following these different state traditions, pension provision in public vs. private schemes strongly differs. Bismarckian schemes not only link contributions closely to employment, but also are heavily defined by the level of earnings. Higher earnings lead to higher contributions, as contributions are typically deducted as a percentage from the gross wage. Similarly, less interruptions during the employment career secure longer contribution periods, and hence higher final pensions. As mentioned above, credits for periods of inactivity may scale up contribution years and pension amounts. The latter might particularly be important for women who show substantively shorter contribution years (according to the ‘Pension Adequacy Report 2018‘ average duration of working lives in the EU28: Women: 33.1, Men: 38 years). Private schemes from employers or financial institutes are naturally less relevant in countries following a Bismarckian path, as income maintenance is primarily provided through the public scheme. Nevertheless, private schemes tend to increase selectively the pension provision of men, foremost due to the mechanism that occupational pensions are typically offered to higher paid professions – jobs that are currently still dominated by men.

Countries limiting their public scheme to poverty prevention, even more link accumulated contributions to inequality in labour incomes. Although, at the bottom of the income distribution, basic or guaranteed pensions might create a gender neutral outcome, contributions to private (occupational and individual) schemes may create substantial gender differences. Private schemes lack mechanisms that account for periods of inactivity more generally. Voluntarism in private schemes may additionally create a lack in provision.

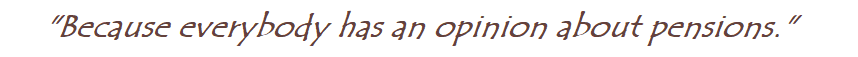

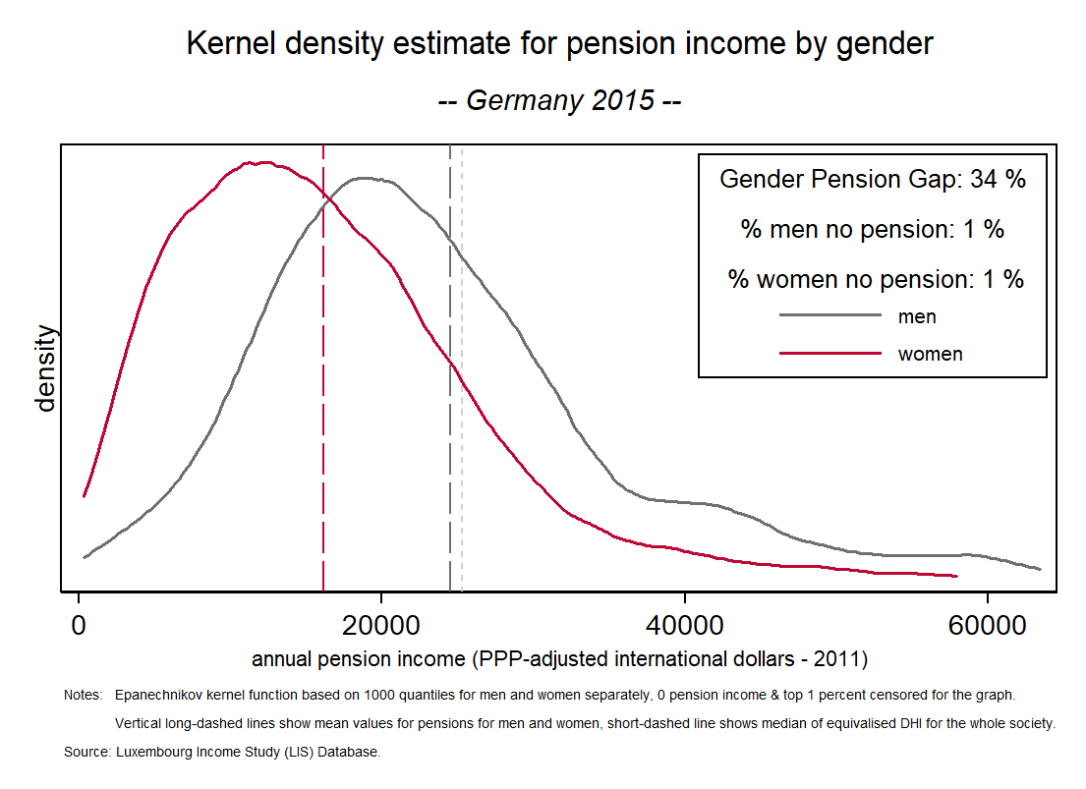

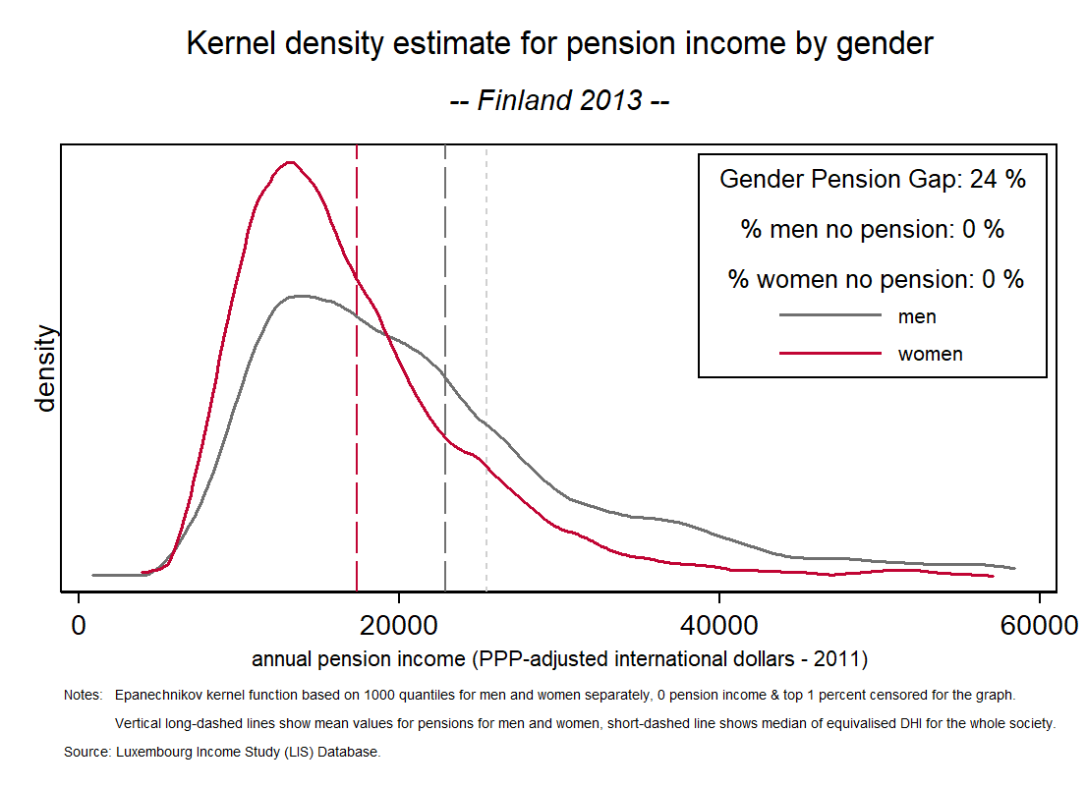

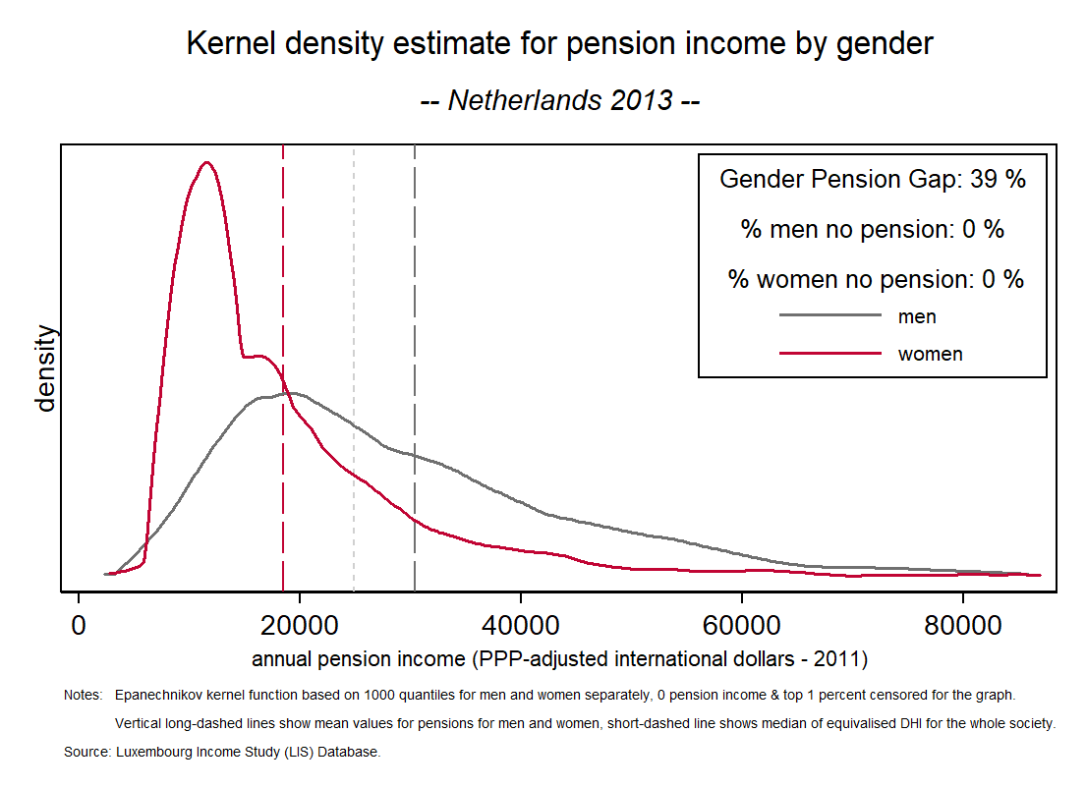

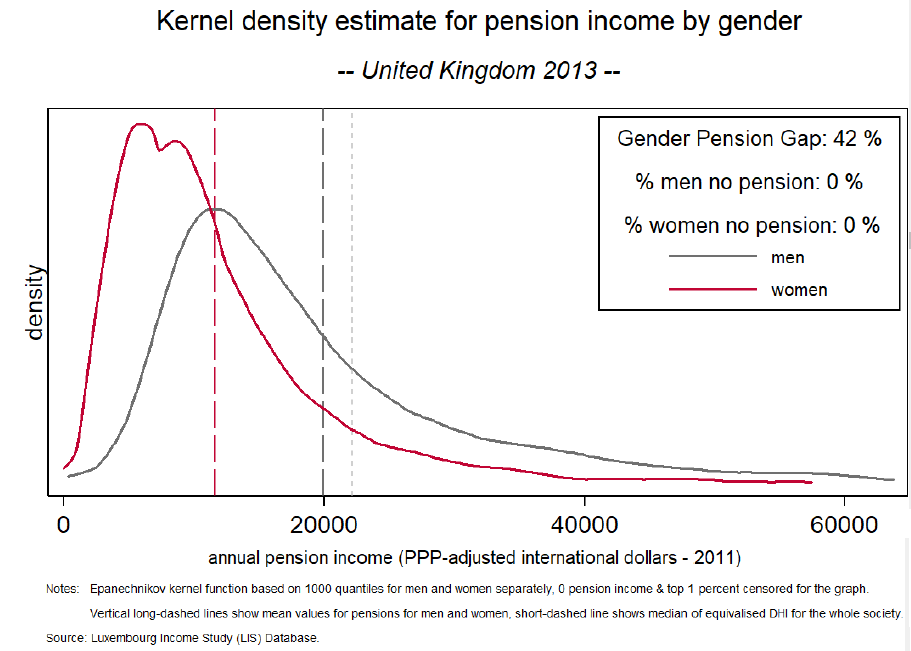

Ok, let us now proceed with the empirics. While presenting these findings, I will elaborate the characteristics of the national pension scheme in each country, explaining the findings. The following graphs visualise pension income distributions. The figures plot Kernel density estimates, which are practically nothing else than a smoothing technique for histograms. The four selected pension schemes provide a broad variation towards their approach to income security among the elderly. In order to minimize the presence of partial pension payments respectively invalidity pensions before switching to retirement, I selected only individuals aged 66 and above. The pension amounts are ppp-adjusted to 2011 International Dollars in order to compare the level of pension amounts across countries. There are two vertical lines in these charts. Each refers to the average pension amounts received by men respectively women aged 66 or above. Besides the legend, I show the level of the gender pension gap, which is derived by 1- (average men – average women) divided by average pension for men.

Germany represents the case of a truly earnings-related system, pension amounts closely relate to contribution-based pension schemes. The pension income distribution reveals a rather smooth density, pension amounts do not cluster around specific values, however, pensions for men respectively concentrate within specific income ranges. The typical range for women is much lower as compared to men, mirrored by the high pension gender gap. The case of Finland represents a combination of targeted minimum pensions – in the past universal minimum pensions based on residency – and tripartite mandated contribution-based schemes. In the graph mostly the shape for women looks different. The access to minimum pensions in case of too low own entitlement from employment, pushes pension amounts for women closer together, reducing the gender gap. Most men have collected sufficient own pension amounts from the various mandated contribution-based schemes, hence the shape is rather similar to the one in Germany. This pattern is even more striking in the case of the Netherlands, where minimum pensions are still generally paid according to years of residence in the country. However, due to the interplay of entitlements from the public scheme, women are left far behind average pensions as compared to men; partly this mirrors the high relevance of part-time employment in the Dutch context which is mostly common among women. In addition, the Dutch scheme does not offer public credits for child raising. Last, let us have a quick look at the British elderly population. The system is known for comparatively low benefits, and the chart reveals a concentration with pensioners receiving low pensions for both sexes, but women in particular. The United Kingdom provides employment-based Beveridge type minimum pensions supplemented by means-tested pension credits. Income maintenance is provided through a mixture of public and contracted out occupational and individual pensions. Mandatory contributions are regulated at a relatively low level in the European context. If people were paying higher voluntary contributions throughout their working career, then it may be linked mostly to their stable employment. Thus, not surprisingly men receive frequently much higher benefits as compared to women, resulting in the highest gender pension gap in this comparison.

This blog post revealed that pension system design matters a great deal for the persistence of gender pension gaps. One closing remark remains. This contribution kept pension income defined broadly, i. e. pension income is analysed jointly as an income mix from all three pension pillars. More detailed analyses, which look the interplay of public and private pension schemes, will provide a more nuanced picture with respect to implications for financial well-being among the elderly. In this sense, stay tuned for more!